Selling a house: Who gives more?

Most homeowners choose an estate agent on the basis of the suggested selling price over other variables such as brand perception, service proposition or the perception of the seller.

In the decision to procurement of real estate services The perception of the company, the valuation of the proposed marketing services and their price, the sensations conveyed by the seller... and the suggested retail price (SRP) of the property all come into play. Above all, the SRP.

Our daily commercial experience teaches us that there is a type of client who bases their decision to contract an agency (often exclusively) on the basis of the PVS of the property proposed by the agency. Consequently, all other things being equal - brand perception, service proposal, seller perception - or even without it, the customer will choose the agency that suggests a higher starting price.

This fact poses a moral dilemma for us at Monapart insofar as we lose proprietary customers to competing companies that generate in them false sales price expectationsand thus strengthen their candidacy. The fair-play and rigorous and truthful advice that are the law in our company are playing against us, but it is no less true that sometimes unrealistic ambitions lead to fortunate sales at unexpectedly high prices. If you would like a free valuation of your property, without obligation, reasoned and without generating false expectations, ask for a free valuation. here.

Are we naïve, is that life, what are we doing wrong? This post is intended as an open reflection and at the same time an exercise that allows me to shed light on a commercial problem that affects us, and I suspect not only us.

[Four preliminary notes and three graphs].

1. Is the selling customer a greedy jerk?

Our experience is that owner-sellers often reject service proposals based on realistic, sound and attractive commercial arguments in favour of other proposals that promise to achieve high sales prices. The reason for this is to be found in the studies of Amos Tversky y Daniel Kahneman that show that the aversion to loss is twice as strong as the illusion of gain.

Here's how it works: Two real estate agencies offer their services to an owner, and although both value the property at €350,000, the first agency suggests a starting price of €410,000 while the second - in a scenario of falling prices - recommends going on the market at a price close to the value, for example €360,000.

And in the head of the owner-seller it happens: Once a anchoring ("Your flat could sell for €410,000") the resistance to accept the evidence ("Based on this detailed analysis, the value of your home is €350,000 and you cannot expect to sell it for much more in the current climate") will be infinite.

Owner-sellers often reject service proposals based on realistic, sound and attractive commercial arguments in favour of other proposals that promise to achieve high sales prices.

As Erasmus of Rotterdam once said: "The spirit of man is so constituted that a lie has 100 times more influence on him than the truth".

2. The problem of prudence: Monapart vs. Other Agency

Last year we experienced the following commercial process (sequentially):

- A client hires us (Monapart) for the exclusive sale of a house that we value by the comparative method at 440.000€.

- Monapart is offering the property for sale at a starting price of €470,000.

- In between, another agency contacts the client and values the property at €510,000.

- After 80 days we received an offer of €410,000 which the client declined to negotiate.

- The exclusive ends and the client hires us again and also another agency. Both agencies are selling the property for 510.000€.

- 60 days later another agency presents a final offer of €430,000 which it suggests accepting and which the client rejects.

- 30 days later Monapart sold the property for €480,000.

And the obligatory questions: Is it acceptable practice to recommend going on sale at €510,000 and then suggest accepting an offer for €430,000? Is it not obvious that Monapart's initial caution would have penalised the seller? Was there a luck factor in finding a buyer who would buy at a high price?

3. Selling and selling yourself are not the same thing.

I have heard some professionals, and I fully agree, say that selling a property means getting more for it than its value..

While making a house "sell itself" requires putting it on the market at a price very close to its value and with sufficient investment in the resources applied, selling a property requires deploying a more sophisticated sequence of marketing and sales actions that add value to the experience and the object of purchase, thus increasing the differential between its value and the final sale price.. The former is available to almost all agencies and quite a few private sellers, while the latter is only available to a few professionals and a few private sellers with positive karma.

Obviously, the first condition for selling a property at a price above its value is to put it up for sale at a price higher than its value. But how much higher?

4. How much time counts?

In the mind of the owner-seller, time never works against him as long as he does not have a time objective for the sale of his property ("I am not in a hurry").

In contrast, among real estate professionals around the world, there is a belief that there is an inverse relationship between time on the market and the final sale price: The longer the property is on the market, the lower the sale price ("This house is burnt").

The reality is that the academic literature on the real estate sector published mainly by US universities (and therefore on the US real estate sector) does not yield conclusive results. On the contrary, there is a complete consensus on the relationship between high starting prices and long marketing times.

Among real estate professionals around the world there is a belief that there is an inverse relationship between time on the market and the final sale price: The longer the property is on the market, the lower the sale price.

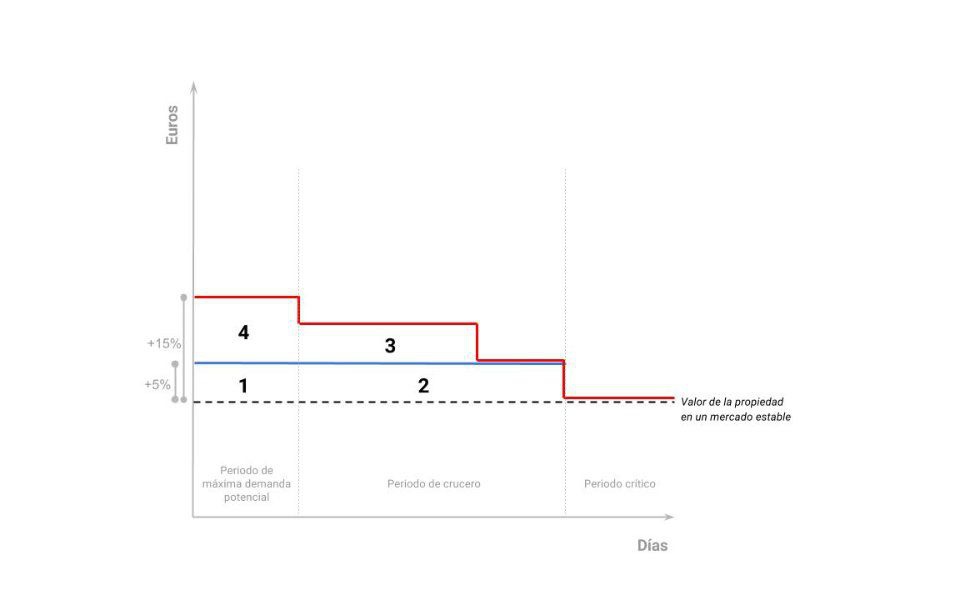

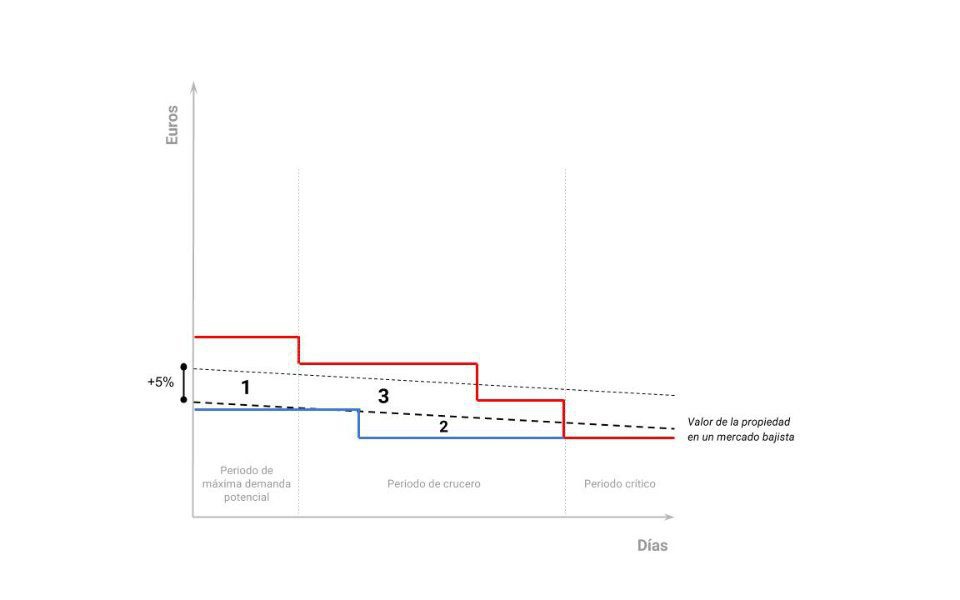

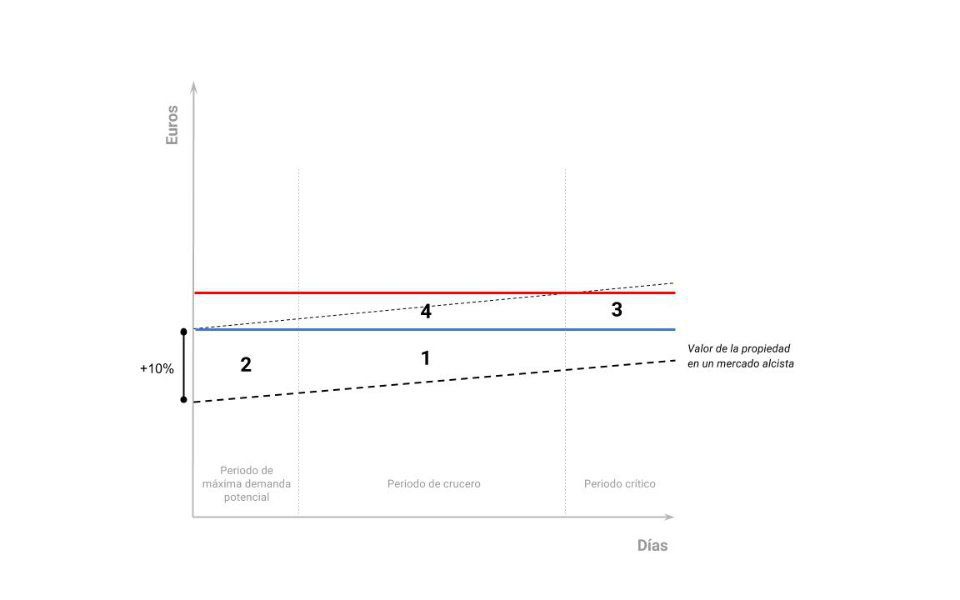

The three graphs below compare two pricing strategies when selling a property: one conservative and one speculative. The first strategy (blue line) seeks to sell early and at a reasonably good price, ideally above value: it is a conservative risk-reward strategy (low risk, low reward). The second strategy (red line) takes the risk of selling late (and some would say even selling poorly) in exchange for opening the door to a less likely sale at a higher price: it is a risky risk-reward strategy (high risk, high reward).

Both strategies are compared in three different scenarios based on the evolution of the value (not the price!) of the house over time: stable, bearish and bullish. In each of the scenarios, the larger numbers (1 to 4) indicate the areas of the graph where the sale is most likely to occur, so that where it says "1" is where I think the time-market conditions are in place - the offer price to sell soon and at a reasonably high price. If I am explaining myself correctly, it will be understood that "1" is always the selling scenario arising from applying conservative strategies, while "3" or "4" mark the areas where more unlikely, but more profitable, sales would occur.

Finally, all the graphs assume a division into three time axis strips (abscissae) following a Pareto Tail logic according to which the highest number of requests will occur at the beginning of the commercialisation and then they will decrease until they "draw" a graph in the form of an aquapark slide. At the end (what I call the "Critical Period") is the moment when, having exhausted the applications from the "pent-up demand", only newcomers to the market are interested in the property.

NOTE: These graphs should be understood as a hypothesis as they are not supported by concrete market data. With them I intend to explain in a visual and didactic way and based on my experience and perception, two commercial strategies and their suitability in markets with different trends.

Graph 1: Selling scenarios in a stable market

The conservative agency (blue) assumes an exit price of VALUE+5% and the speculative agency (red) assumes an exit price of VALUE+15%. Insofar as the conservative strategy foresees a short sale, it could even propose an a priori price strategy with no fluctuation over time. In contrast, the speculative strategy assumes from the outset the need for progressive declines as time progresses and an unlikely sell-off at a high price does not occur (if at all).

I assume that any price above 15% of the value of the house is in a price disincentive zone where no purchase offers are made.

Graph 2: Selling scenarios in a bear market

The conservative agency (blue) assumes an exit price of VALUE-2% and the speculative agency (red) assumes an exit price of VALUE+10%. The conservative strategy aims to sell "at value" at some point close to the crossover between the value curve (downward) and the price curve. If the sale does not occur, then a new price (let's assume 5% below) should be set to look for a new moment of curve "intersection".

Traditionally in this scenario, the agency, applying a speculative strategy, always places its prices close to the VALUE+5% range where it knows that, even in a bearish scenario, there may be an unlikely sale by a buyer "in love" with the property. The obvious risk is to "overshoot the brakes" and that, insofar as the value has a downward trend, selling later is selling worse.

Graph 3: Selling scenarios in a bull market

The conservative agency (blue) starts from an exit price of VALUE+10% assuming that in a bullish scenario, the fear of buying above value is lower. The speculative agency (red) reaches an identical conclusion, but its own nature requires it to position itself in a higher risk-return binomial, so it will choose to exit at VALUE+15%, for example.

Both expect to sell before they reach the point at which the rising value curve crosses the constant price curve, as it is likely to do sooner or later.

Conclusion

In all the graphs I have assumed the coexistence of two companies applying different marketing strategies, but I tend to think that both could be implemented by the same agency, just as a financial advisor can invest our savings in government bonds or in shares of listed companies.

Agencies must "modulate" the relationship between value, price and time when designing the appropriate strategy for the sale of a property, taking into account: (1) the risk profile of our own company; (2) the risk-benefit ratio requested by the client; and (3) the market trend.

On the other hand the "sell high" expectations of owner-sellers should not lead some to make promises they know they will not be able to keep in order to get people to hire their services.. Others, too, must curb their tendency to minimise customer risk by seeking a quick sale, as this often harms their economic interests.