For a new new work (part I)

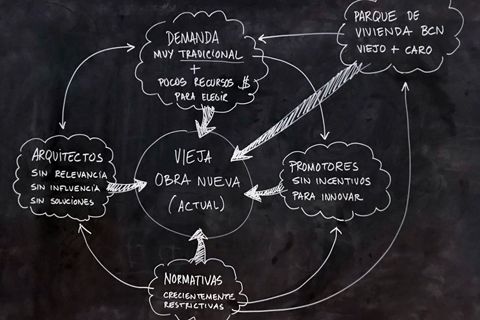

New work is old because there is a combination of socio-demographic factors, supply and demand balance and pernicious sectoral inertia.

[Introductory note: In this article no distinction is made between new construction corresponding to new buildings and new construction resulting from major refurbishment operations].

The umbrella may be the object that has evolved the least since its invention. The person who teleports an electron or goes to the moon and back, or remotely performs open-heart surgery... all compromise the 50% of the upper half of the body to endure a 2nd century BC Chinese invention when it rains. There is no dignified option. Then comes the housing. Almost all the housing is old, the already old and the born old. I want to talk about the latter, the Old New Work.

I will argue in an alternative way to the usual one on the housing problem - speculators, foreign demand, the precariat, millennials, etc. - although not necessarily in opposition to it. I think it is a complementary and not exclusive argument.

I believe that the new work is old because (in order of relevance):

- The demand for traditional housing is in iron health. Recall how Steve Jobs lived in this hobbit house and how we have learned to live from our parents, and so our adult housing partly (half) replicates our childhood housing, which is always older.

- By virtue of the previous point, housing manufacturers - the supply side - have no incentive to innovate, but in those aspects that affect their bottom line - production technologies and sales technologies - which they have adopted at best.

- The most interesting cities, those that attract global talent and elites who maybe (maybe!) might be open to experimenting with (and paying for) new housing, are "finished" cities with almost all of their building stock pre-dating 1980. [The Console Atari 2600an electronic device with a wooden beautifier, was launched in Spain in 1980].

- Cities - these cities - are home to 55% of the world's population, which will grow to 68% by 2050. In a scenario of perpetual over-demand, old (existing) housing is already at the price limit. or rent that demand can pay. [The "I" in innovation is nothing more than the commercial viability of "R&D". Who pays for it].

- The regulations -this is the favourite argument of developers- of building, habitability and urban planning are increasingly restrictive and hinder innovation. [But isn't this the case in any industry? Sectors such as automotive, food, fashion... innovate continuously despite being heavily regulated].

- Architects in academia have been pretending to innovate for a thousand years. moving things around to make housing more "flexible". A horizontal, turn-based version of the myth of Sisyphus.

To sum up:

(1) Cities such as Barcelona offer a residential stock that is on average 70 years old.

(2) This housing is at the limit of what a growing, resigned and residentially conservative demand can afford.

(3) Meanwhile, housing producers, constrained by regulations and feeling comfortable in an undemanding market, replicate the same building over and over again with small incremental improvements and stylistic tweaks decided by

(4) architects relegated to the role of image consultants.

It is therefore, of course, a combination of socio-demographic factors, supply and demand balance and pernicious sectoral inertia. Everything plays in favour of those who buy a home not demanding better and more suitable to their time and need of use. But what exactly is the substance of this "better and more suitable to their time and need of use"?